The story behind FarmPlus

and how an evening chai session with the boys can turn ideas into startups

Disclaimer: This is definitely not a technical blog post. Think of this as my attempt to document something important that happened to me, somewhere between “dear diary” and “academic paper that puts people to sleep.”. I use “we” a lot more in this blog because although I was responsible for building the tech, this was very much a team effort :)

All of us underestimate the importance of dairy in our lives. Our morning coffee, the cereal we grab for breakfast, the cream in our pasta sauces, and countless other foods we consume daily all depend on a reliable supply of fresh, high-quality milk. Yet most of us never stop to think about the complex systems and challenges that dairy farmers face to get that milk from farm to table.

This is the story of how a casual evening conversation over chai led to FarmPlus, a dairy-tech startup that won first place at the 2022 Hopkins New Venture Challenge and was subsequently incubated at the JHU Spark Incubator.

The Backstory: The evening that started it all

The amber glow of our apartment’s overhead light cast familiar shadows across the worn wooden table as steam rose from our chai glasses that spring evening in 2022. In India, there’s a saying - “Chai pe Charcha” (chats over chai) - and there’s a whole tradition around these tea sessions. What began as our obligatory evening ritual would transform into one of those conversations that redirects the trajectory of our semester.

My roommate, our in-house “Milk Connoisseur” with deep ties to India’s dairy industry, studied me with the intensity of someone about to pose a challenge that would make you question your life choices. “You keep talking about building health monitoring devices,” he said, leaning forward, “but can you make a health monitoring system that works on a cow?”

The question hung in the air like the aromatic cardamom from our chai. At first, I thought this was absurd—a playful provocation born from too much chai and late-night academic ambition. My roommate began unraveling the intricacies of dairy health monitoring, explaining the parameters and metrics that mattered to farmers, the economic pressures they faced, and his personal experiences about the industry feeding billions.

That evening sparked something bigger. In the next few weeks, we decided to turn this crazy cow idea into our submission for the Johns Hopkins New Venture Challenge. We spent our time researching everything we could about dairy farming and figuring out if we could actually build something that worked. The more we dug into veterinary research, the more we realized there weren’t many studies using modern monitoring devices on cattle. That was actually great news for us—it meant we’d found a real problem that nobody else was solving yet.

The Problem: Discovering the hidden complexity of bovine economics

Designing a fitbit for cows proved far more nuanced than our initial enthusiasm suggested. The dairy industry operates on a sophisticated economic model that most outsiders never fully grasp. The foundation of this economy rests on a fundamental biological truth: a cow’s most valuable period begins only after pregnancy and childbirth.

Here’s the economic reality that drives every decision on a dairy farm: cows can only produce milk after giving birth to calves. This lactation period, which can last up to 305 days, represents the primary return on investment for farmers. During this time, a single high-producing dairy cow can generate 6-7 gallons of milk daily—translating to thousands of dollars in annual revenue. But this economic engine depends entirely on successful breeding, which brings us to the heart of our technological challenge.

The art and science of bovine reproduction timing is where fortunes are made and lost. Farmers must identify the precise 12-24 hour window when a cow is in estrus (heat) and ready for insemination. Miss this window, and you’ve lost a month—potentially thousands of dollars in delayed milk production. Get it right, and you’ve set in motion a carefully orchestrated biological and economic cycle that sustains the farm’s profitability.

This requires developing tools to identify when a cow is ready for insemination with unprecedented precision. We learned that a cow’s internal heat—distinct from mere body temperature—serves as a reliable indicator for the ovulation cycle. As cows experience this internal heat surge, they exhibit specific behavioral patterns: increased vocalization (mooing), restless head movement, and heightened activity levels. These subtle signs, when properly detected and analyzed, become the farmer’s early warning system for optimal breeding timing. As the tech lead, it was my job to design a system that would augment the farmer’s system design.

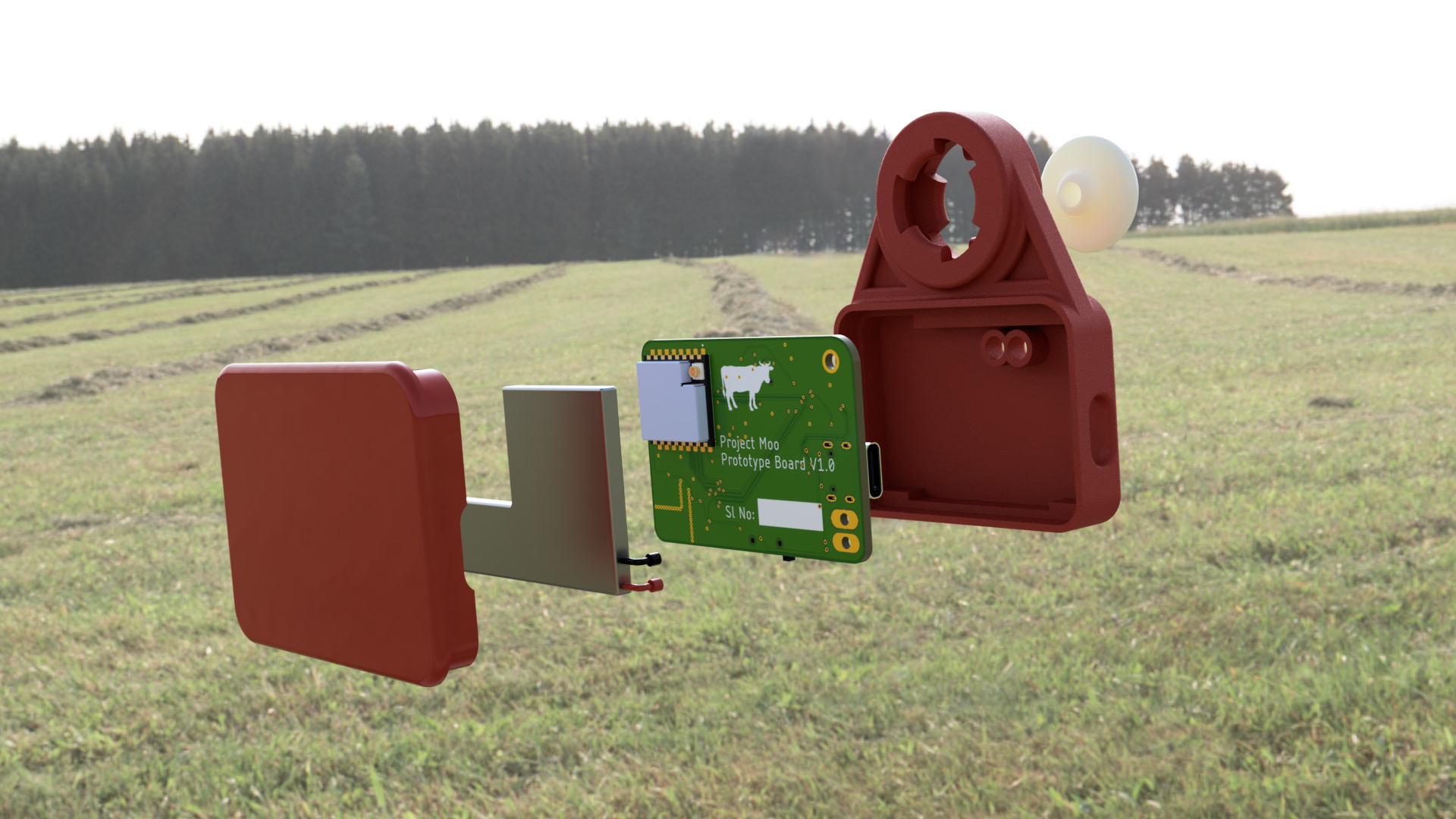

The technical challenges were formidable. Cows possess a layer of fur that makes photoplethysmography (infrared blood monitoring) sensing nearly impossible, since IR signals cannot bounce back effectively through fur. This limitation forced us to reconsider device placement entirely. While most existing dairy monitoring solutions employ collar-mounted devices, we had to pioneer an ear-mounted approach—a decision that would reshape our entire technical architecture and manufacturing strategy.

Building the Solution: The hardware + techstack

We centered our approach around an ear-mounted device designed to survive the harsh realities of farm life while delivering laboratory-grade data accuracy.

Hardware Design: With the help of an old friend, an expert in electronics/PCB design, we engineered a rugged, waterproof housing that protected multiple sophisticated sensors—accelerometers for movement tracking, temperature sensors for internal heat monitoring, an on-board microphone for capturing the intensity of vocalization, and specialized algorithms to detect rumination patterns. The device needed to function flawlessly for several years with minimal human intervention, enduring everything from torrential rains to subzero winters. One of our coolest design challenges was the charging system. Since cows return to specific docking pods in the shed at the end of each day, we designed our device to charge wirelessly when they were docked—kind of like a Tesla at a supercharger station. We used induction charging with a head coil that worked similar to the coils humans wear during MRI scans, so the device could power up overnight while the cow rested.

Connectivity: The scale of American agriculture demanded a connectivity solution as ambitious as the farms themselves. With the average U.S. farm spanning 500 acres, conventional Bluetooth or even long-range WiFi proved woefully inadequate. Drawing inspiration from cellular tower technology, we implemented a mesh network system using long-range, low-power radio frequencies. This innovation allowed data from individual cows to flow seamlessly to a central hub, even across vast properties with limited technological infrastructure.

Data Analytics: We planned on developing machine learning models capable of identifying patterns indicative of health issues, breeding readiness, and herd optimization opportunities. Our system learned from each farm’s unique conditions and herd characteristics, becoming increasingly accurate as it absorbed more data. The algorithms would be able to distinguish between normal behavioral variations and significant biological events, reducing false alarms while ensuring no critical moments were missed.

User Interface: We crafted a deliberately simple, intuitive dashboard that translated complex biological data into actionable insights. Rather than overwhelming farmers with technical minutiae, our interface prioritized critical alerts and could dispatch notifications via text message or email when specific cows required immediate attention.

Customer Validation and Outreach: Learning from the field

Our journey from laboratory to barnyard began with extensive outreach to dairy operations across Maryland, Alabama, and Wisconsin. These video calls weren’t just quick check-ins—we spent hours learning how farms actually operate day-to-day.

Through virtual farm tours and video calls with dairy operations, we got our first real glimpse into how dairy farming actually works. We learned how farmers navigate their 4 AM milking routines, the careful attention they pay to individual animal health, and started to understand the countless decisions they make daily to keep their operations running. One thing that really surprised us was how open many of the farmers were to trying out new technology—we’d expected them to be much more conservative and resistant to change, but they were actually eager to test anything that might help their operations. These virtual experiences taught us that any technology we built had to fit into farmers’ existing routines, not force them to completely change how they worked.

Our connection with one of India’s largest dairy cooperatives provided invaluable global perspective. We learned how different climates, economic conditions, and cultural practices influenced technological adoption. What worked in Wisconsin’s climate-controlled facilities might require substantial modification for India’s tropical conditions or larger-scale operations.

The Incubator Experience: From academia to entrepreneurship

Selection for the JHU Spark Incubator marked our transition from academic theorists to startup practitioners. The program provided far more than funding and workspace—it offered access to a network of mentors, advisors, and fellow entrepreneurs navigating similar challenges in transforming ideas into sustainable businesses.

The most jarring adjustment involved pace and iteration cycles. Academic research thrives on careful, methodical progress over extended timeframes. Startup culture demanded rapid prototyping, quick pivots based on market feedback, and the courage to abandon elegant solutions that didn’t serve customer needs.

We learned to embrace failure as an essential learning mechanism. Our initial hardware design, while technically sophisticated, was overcomplicated and prohibitively expensive to manufacture. Customer interviews revealed that farmers valued simplicity and reliability over advanced features they might never utilize. This feedback forced us to make difficult decisions about feature prioritization, ultimately leading to better product-market alignment.

The process taught us to kill our darlings—to abandon technically impressive components that didn’t directly solve customer problems. This discipline, painful for engineering minds enamored with technical elegance, proved essential for commercial viability.

Lessons Learned: Wisdom from the intersection of technology and tradition

The FarmPlus journey illuminated fundamental truths about entrepreneurship, technology development, and the delicate art of introducing innovation into traditional industries:

Customer-Centric Design: Technical elegance means nothing without solving real problems for real customers in ways they’re willing to pay for. Our time spent in understanding daily routines and listening to farmer concerns, proved more valuable than any theoretical market research. These conversations taught us that farmers are sophisticated consumers who evaluate technology through the lens of practical utility and return on investment.

The Power of Interdisciplinary Teams: Our group’s diverse backgrounds in biomedical engineering, finance, sales, and business management created a synergy that none of us could have achieved individually. The combination of technical depth and business acumen proved essential for tackling both engineering challenges and market development needs.

Iterative Development Philosophy: Academic perfectionism demanded that we complete solutions before seeking feedback. Startup methodology taught us that early, frequent feedback—even on imperfect prototypes—accelerated progress and improved outcomes. This shift from perfection-driven to iteration-driven development proved transformational.

Market Education Challenges: We underestimated the effort required to educate potential customers about our solution’s value proposition. Many farmers harbored skepticism toward technology, having experienced previous “innovative” solutions that failed to deliver promised benefits. This skepticism actually strengthened our approach—it forced us to become better communicators and ensured our solution adhered to Kelly Johnson’s K.I.S.S. principle (Keep It Simple, Stupid; developed during his work on the SR-71 Blackbird and other aerospace marvels).

Regulatory Complexity: While our device didn’t require FDA approval, we navigated various agricultural regulations and industry standards. This compliance work added complexity but also created competitive barriers that could protect us from future competitors.

The Bigger Picture: Technology’s role in feeding the world

FarmPlus represented more than a business venture to us— and it served as my introduction to the intersection of technology and agriculture, a domain with enormous potential for positive global impact. Agriculture feeds humanity, but faces unprecedented challenges from climate change, population growth, and resource constraints.

I believe technology holds genuine potential to make agriculture more efficient, sustainable, and profitable. However, successful agricultural technology requires entrepreneurs who understand both technical possibilities and practical industry realities. Our experience taught us that effective ag-tech demands deep empathy for farmers and their challenges, not merely technical expertise.

The dairy industry exemplifies this balance. While consumers see only the final product in grocery stores, farmers manage complex biological systems involving animal welfare, environmental sustainability, and economic viability. Technology that serves these multiple stakeholders simultaneously creates lasting value and sustainable business models.

Looking Forward: Lessons for future agricultural innovators

The FarmPlus experience revealed principles that extend beyond our specific solution. These are my two cents for any future agricultural technology developers from my journey:

First, spend significant time understanding the human element of a traditional system. Technology adoption in agriculture depends heavily on trust, reliability, and seamless integration with existing practices. Farmers are sophisticated decision-makers who evaluate innovations through multiple lenses: economic impact, operational complexity, and long-term sustainability.

Second, recognize that agricultural markets operate on different timescales than typical tech markets. Product development cycles, customer acquisition, and revenue generation all follow patterns distinct from consumer technology or B2B software markets. Patience and persistence become essential entrepreneurial qualities.

Third, consider the global implications of agricultural innovation. Solutions developed for American farms might require substantial modification for international markets, but the fundamental challenges of feeding growing populations remain universal. Scalable agricultural technology has the potential to address some of humanity’s most pressing challenges.

As for my team, we decided to take a hiatus from FarmPlus after graduation to focus on our full-time jobs. But we’re all still passionate about making an impact in this space and incredibly proud of what we achieved together. I guess life really does throw the occasional curve ball—sometimes the timing just isn’t right, even when the idea is solid.

The Accountability Moment

As I mentioned in my bio, my co-founder and best friend insisted that I write this story and take “public accountability” for our FarmPlus journey. Consider this my fulfillment of that promise. Sometimes the most powerful motivation comes from best friends who refuse to let you forget the ambitious ideas you’ve pursued together over late-night conversations.

To anyone reading this who harbors their own “crazy startup idea” brewing during informal conversations with friends—don’t merely discuss it. Build something tangible, test it rigorously, and pursue it with genuine commitment. You might discover surprising insights about both the market opportunity and your own capabilities along the way.

The intersection of technology and traditional industries offers fertile ground for innovation, but success requires humility, persistence, and genuine respect for the wisdom embedded in established practices. My FarmPlus experience taught me that the most profound innovations often emerge not from disrupting traditional industries, but from thoughtfully enhancing them with modern capabilities.

What began as an evening conversation over chai evolved into a genuine startup experience that taught us invaluable lessons about entrepreneurship and opened our eyes to technology’s incredible potential for transforming traditional industries. Not bad for a Tuesday night study break.

If you’ve come this far, thank you for your attention and patience ~ Cheers, A